Right there, along a two-block stretch in the heart of one of the country’s most storied metropolises, lies a history of pride, struggle, and perseverance that is symbolic of an entire nation.

In its infancy and at first glance, Detroit’s Birchwood Street didn’t resonate much differently than any other in the once typically race and income mixed neighborhood born of the early 1940s: whites lived on one side and blacks the other, the boundaries divided by a 6 foot tall, and a foot thick wall known as “Detroit’s Wailing Wall.”

“That was the division line,” reflects Eva Nelson-McClendon, who at 79 still resides in the one-story home she purchased more than half a century ago. “That was the way it was.”

Yet now, for some that darkness serves as enlightenment. Although the wall remains, its drab overtones and graffiti-stained facing replaced by a slew of images and messages advocating the kind of social equality and racial justice the people want today, it once served as a symbol of the exact opposite of. More recently, a faith-based nonprofit began using its grounds as a meeting place for men in need of work and struggling to find their way through the Great Recession that never seems destined to end.

A drawing of Rosa Parks boarding a bus that sparked the Alabama bus boycott, and a painting of Sojourner Truth navigating her way around the underground railroad, as a frustrated and chagrined KKK member looks on, are all now prominently featured on the wall. Seemingly as stark remainders of the kind of determination and resolve, one needs to overcome even current circumstance.

"Of course, she has a light - and the light symbolizes leading the way," Chazz Miller, the artist who designed the mural beams of Truth. “The Ku Klux Klansman has a burning cross and is pissed she got away.”

"Of course, she has a light - and the light symbolizes leading the way," Chazz Miller, the artist who designed the mural beams of Truth. “The Ku Klux Klansman has a burning cross and is pissed she got away.”

Indeed, race has always been and remains a point of contention in the city where two of the nation’s most violent race riots took place within a 25-year span of one another, and where a white developer’s plan for building that aforementioned wall were approved by federal officials as eager to preserve separation among its citizenry as he was.

Over the last year, the state’s governor took over the city after declaring it in a financial emergency and throughout the recent 2012 Election season, many would-be voters accused city leaders of attempting to disenfranchise blacks and other minority residents. As a whole, Detroit holds one of the nation’s highest unemployment rates, and even that is nearly two times higher for black workers.

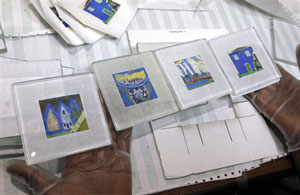

Jason Garland, 26, is one of those so affected. A one-time automotive worker, he’s been out of work now for more than a year and works with a not-for-profit whenever he can. Between making coaster sets and affixing them to the mural, Garland is also learning history.

Before working at the site of the mural, he professes to not having any idea what the wall was meant to symbolize or why it holds so much social significance, even though he lived just steps away and ventured past it almost daily.

"I used to always say, 'What is that?'" he admits. It’s growth and maturation like that which gives Miller hope for a new Detroit. Though countless of abandoned and trashed homes stand within steps of her masterpiece, in that he somehow sees the promise of a new dawn.

"I used to always say, 'What is that?'" he admits. It’s growth and maturation like that which gives Miller hope for a new Detroit. Though countless of abandoned and trashed homes stand within steps of her masterpiece, in that he somehow sees the promise of a new dawn.

"It's really up to us to not cry on what's gone," he said. "Let's focus on what we have. ... We need to get people out do these kinds of projects so they can have conversations and get to know each other and find out who their neighbors are. The spirit of Detroit motivates us to work hard and persevere, to keep going.”

It’s a mindset, Nelson-McClendon can relate to. “Did it make me angry to see that wall up there? It was something you grow accustomed to seeing… getting angry over it is not going to change anything. What was important was bringing up my kids and getting them to get an education so they wouldn’t have to be bothered in the future. You’re not going to stop progress, don’t care how hard you try.”