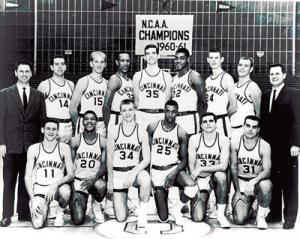

Tom Thacker led the University of Cincinnati Bearcats to three straight NCAA championship games from 1961 to 1963. In the pros, he won three national championships in three different leagues. “When it came to winning championships, nobody was better than Tom Thacker,” sports writer Michael Perry wrote in his book Tales From Cincinnati Bearcat Basketball.

But before Thacker was a champion, he was a talented African-American youth playing basketball in a segregated world.

Tom Thacker grew up in Covington, KY, a river town facing Cincinnati from the southern bank of the Ohio River. Covington was the geographic north peak of the segregated South, but the general rules of “separate but equal” still applied. Like most African-Americans in town, he attended the all-black William Grant High School.

Former state high school athletics commissioner, Louis Stout, calls Thacker “the greatest Grant High product.” He averaged 31.7 points per game as a junior and 33.8 as a senior. Thacker credits coach Jim Brock for preparing his team for the world both on and off the court. “He taught us how to hold and how to fold,” he says.

The nation was slowly integrating and so was Thacker. “The days of segregation were pathetic and funny at the same time,” he says. “We knew the white kids you could play with and those you couldn’t. We didn’t violate those boundary lines.”

The 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision didn’t erase those lines overnight. Grant’s Warriors traveled great distances to play other African-American schools. In smaller towns where no black hotel existed, Thacker and his teammates stayed the night with the home team’s families. In some cases, they had to cross state lines to get a room.

African-American schools also consistently received inferior equipment and uniforms. Grant’s gymnasium was only good for practices. As token integration began, some black basketball stars transferred to the better-equipped white schools, breaking apart talented squads.

In the late 1950s, white high school athletic associations began absorbing the African-American leagues in the South. White coaches were reluctant to schedule the black schools—race and record mattered—but couldn’t avoid these skilled teams in post-season tournament play. A white boycott would end their season by forfeiting a tournament game. Thacker’s team claimed district and regional titles, causing some white schools to add the Warriors to their schedule.

Discrimination did not disappear from the game. As the leagues merged, most all African-American referees were phased out, leaving only token black officials and biased judging for most interracial games. “The officiating did look kind of shaky at times,” says coach Brock, whose coaching philosophy included winning early so close calls couldn’t cost them the game.

Thacker remembers the bias officiating a little more vividly. “It was very obvious. It was like black and white. That’s how obvious,” he says. “The referee is going to favor the culture he was raised up in. That’s human nature.”

The unique cultural difference in black and white playing styles and the white officials’ familiarity with their own race unfortunately determined close calls too often. “We made unique spin moves. We played much faster. Higher above the rims,” he says. “We played at a different pace, at a different beat, we heard a different sound.”

The variances in game-tempo may be what ended Thacker’s high school career in 1959 short of the state championship in an 85-84 loss.

Thacker went on to play college basketball for Cincinnati, where winning championships became easier but prejudices still surfaced. Thacker attests, “I heard more name calling in college than I did in High School.” In Texas, the crowd chanted racial epithets like “Sambo” at the four visiting African-American players on the floor. Ironically, Thacker and his black teammates were refused service in a downtown Louisville greasy spoon after winning the 1962 NCAA championship. Once, in an Alabama airport, Thacker and his teammates enjoyed a cigarette in a “colored-only” restroom, knowing their white coach wouldn’t catch them.

But Thacker was held to runner-up status only under Jim Crow.

“That was one of the things I always regretted. I never won a high school state championship,” he says. “I got close, but never won it.”

Thacker’s contribution to the game and other milestones overshadow any deep bitterness. After winning national titles in 1961 and 1962, his Bearcats lost in his final college game, 60-58 to Loyola. But “we made history, seven of the ten starters that year were black,” he says.