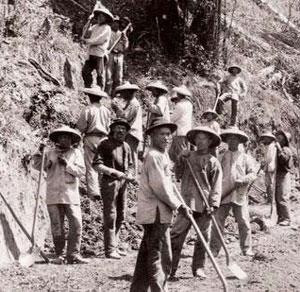

In 1869, the final spike was set on the first American transcontinental railroad. It was a milestone connecting the east and the west of the United States. While the Union Pacific built the eastern tracks with the ease of flatter lands, the Central Pacific Railroad Company faced a tougher time going through the rough terrain of the Rocky Mountains. In addition, the Central Pacific faced the hindrance of not having enough workers since most men did not wish to risk their lives. Therefore, they decided to hire “outsiders,” the Chinese, who were coming to the west coast for better opportunities than their native lands, could offer.

However, they were not welcomed with open arms; rather they faced skepticism because they appeared to have delicate, effeminate hands and were too small for a giant project. Even after the successful completion of the railroads, Stan Steiner in his book, Fusang: The Chinese Who Built America, says, “Men in China not only built the Western half of the first continental railroad; they built the whole or half of nearly every railroad line in the West. In spite of that or perhaps because of it, their labors were belittled and their heroism disparaged over a century afterward…” Over the decades, the contributions of the Chinese were forgotten as whites became resentful about “the little yellow men” that did so much work in such little time on the railroads.

How did the Chinese come to work for the railroads? Most of them were young men in search of adventure and job opportunities. Despite being paid lower rates than whites doing the same work, building railroads was still better pay than what they could have earned as farmers in their China.

In 1863, the Central Pacific Railroad Company laid only 31 miles of track. They needed 5,000 men to do the job, but only had 600 workers. Since the Chinese had already helped on smaller railroads, it was suggested that they could work for the transcontinental railroad. Naysayers made their complaints (despite already proving they had experience), that led to a railroad official’s retort that they had built the Great Wall of China.

The Chinese perfected blasting and drilling of the rock, riding in large hanging woven baskets that could fit several men which carried them up and down the mountainsides. Many perished in explosions and accidents. Despite the dangers, they pushed on and even managed to set a record in railroad building laying out 10 miles of track in one day. It was unprecedented in a time of manual labor and without the conveniences of modern machinery.

Finally, the tracks reached Promontory Point and met up with the eastern tracks of the Union Pacific Company, and by the end of the project; the Chinese totaled two-thirds of the staff. Afterwards, the Chinese continued to build railroads from Alaska to Texas.

So were there notes of gratitude for such an accomplishment? Yes, the Chinese received acknowledgement for the fact that the railroad would not have been completed in the set amount of time without their help. A railroad builder, West Evans, asserted in 1876, “I do not see how we could do the work we have done without them; at least I have done the work [on the railroads] that would not have been done if it had not been for the Chinamen.”

Despite the praise, over time, the prejudices became more and more prevalent. In 1879, novelist Robert Louis Stevenson, noticed on a California trip, how poorly the whites treated the Chinese, regardless of the fact that they built the railroads that afforded all others the luxury of traveling across the nation.

Over the years since the railroad began its operations, as author Stan Steiner reported, “the Chinese railroad men had been rendered faceless. They had vanished from history.” Professor Madeline Hsu of Asian American Studies at the University of Texas-Austin says, “the absence of Chinese from the celebrations at Promontory Point, where the Transcontinental Railroad was finished, was perhaps the most glaring example [of the lack of Chinese representation].”

Recently, acknowledgment of the historical contributions of the Chinese has gained momentum. Mian Situ, a Chinese American painter, has been instrumental in highlighting Chinese American history and has maintained a loyal following. Just this year, the History Channel devoted a portion of their documentary series, America: The Story of Us, to the contributions of the Chinese in the building of transcontinental railroad.

Sources:

Fusang: The Chinese Who Built America, Stan Steiner, pages 128-140, First edition, New York: Harper and Row, 1979.

Madeline Hsu, PhD, personal communication, June 12, 2010.