March 2, 1955 was the wrong day to mess with Claudette Colvin.

She and her classmates at Booker T. Washington High School in Montgomery, AL, – one of two all-black high schools in the city – left class early that late winter's day so teachers could attend a faculty meeting. The weather was unusually muggy and summerlike – a good day to ride the bus home.

Colvin, an energetic and bespectacled 15-year-old, walked downtown, got on the bus, paid the nickel fare, and picked a window seat about halfway down the aisle. Three of her schoolmates sat next to her. “We were sitting in the section we always sat in every day,” Colvin says.

The bus filled with passengers as it made its way down Dexter Avenue. A white woman climbed aboard and stood squared jawed in the aisle expecting Colvin and her friends to give up their seats. The woman did not want to sit down on the empty seat across from Colvin. After all, this was the South, and the home of Jim Crow. Surely, this black girl knew her place.

Colvin did know her place. For weeks, Colvin's teachers had regaled students with stories of the African-American struggle for equality. Those stories were still fresh in Colvin's head on that fateful day. Therefore, when the driver shouted, “I need those seats,” Colvin paid him no mind. While her friends heeded the motorman's orders and scurried to the back, the 15-year-old stayed in her seat.

Colvin had had enough of Montgomery's racist segregation policies. She had had enough of the separate entrances and water fountains. She knew what the constitution said. It was her right to sit anywhere she wanted.

What happened next changed Colvin's young life forever, and moved the nation down the road of racial justice. The police boarded the bus, yanked Colvin off by her wrists, and tossed her in jail for violating a city law ordering blacks to give up their seats to whites. “I wasn't going to voluntarily walk off the bus, so the police manhandled me,” Colvin remembers.

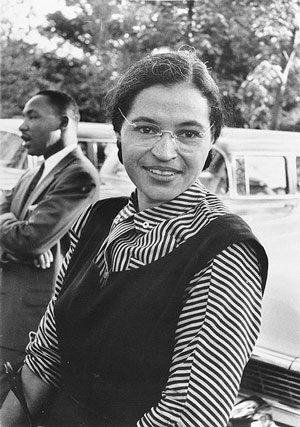

After the jailhouse's doors slammed shut, Colvin found a lawyer and fought the charges. Colvin had fired one of the first shots of the civil rights movement a full nine months before Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of the bus. Parks' action the following December sparked the Montgomery bus boycott. While the world remembers Rosa Parks, the story of Claudette Colvin found its way into the dustbin of history.

Now, 55 years later, writer Phillip Hoose has finally set the record straight in his Newbury Award-winning book, Claudette Colvin: Twice Toward Justice. Hoose provides a mesmerizing and in-depth account – much of it in Colvin's own words – of the teenager's actions that steamy southern day.

Yet, Colvin's story is more than just the narrative of a rebellious teenager. It is also the story of how the civil rights movement relied on thousands of Claudette Colvin’s to wrestle Jim Crow to the ground. Colvin's story is also the tale of how black leaders handpicked their martyrs. Although Colvin was one of four women plaintiffs in the court case that successfully overturned Montgomery's bus segregation laws, she was not the public face of the boycott.

Why didn't Colvin receive the same recognition as Parks? Black leaders in Montgomery deemed Colvin unfit to be a role model. Colvin's parents weren't really her parents; an aunt and uncle who were domestic laborers that lived on a dirt road 30 miles from town raised her. Moreover, some complained Colvin was combative and mouthy, not exactly the type of person the movement wanted as its standard-bearer. When Colvin got pregnant a year later, many people turned their backs on her.

“The leaders of the civil rights movement understood the dynamics of a good symbol,” says Kevin Boyle, a professor of history at Ohio State University. Rosa Parks, a seamstress and activist, was a good symbol. Claudette Colvin, a feisty teenager, was not.

“The leaders of the civil rights movement understood the dynamics of a good symbol,” says Kevin Boyle, a professor of history at Ohio State University. Rosa Parks, a seamstress and activist, was a good symbol. Claudette Colvin, a feisty teenager, was not.

More than half a century later, Colvin does not bear any animosity toward Rosa Parks who got all the attention. “I knew Mrs. Parks had the looks and the experience required to motivate all these people and create a successful boycott,” Colvin says.

Colvin was not the first to stay seated. Several other Montgomery women had previously defied the rules. Most left the bus quietly, paid their fine, and went on their way. Yet Colvin was different. Armed with the anger of the centuries, she fought her arrest in court. “She wasn't the first to keep her seat,” Hoose says, “[but] she was the first to fight it.”

Colvin often says the ghosts of former black leaders such as Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman moved her. She credits those spirits with telling her to “Sit down girl!” “I tell people that history had me glued to the seat. Harriet Tubman was pushing down on one shoulder, and Sojourner Truth was pushing me down on the other shoulder.”

For a 15-year-old black girl to stand up to the institutional racism prevalent in the South in the 1950s was nothing short of remarkable. She risked losing everything, including friends, family, and even her life.

“I can only begin to imagine what it felt like,” says Rhonda Y. Williams, an associate professor of history at Case Western Reserve University. “I can imagine the fear as well as the fortitude and steadfastness. She (Colvin) knew there was the possibility of lynching and police beatings. She knew what happened to people who bucked the status quo.”

Colvin's bravery came at a price however. Classmates shunned and ridiculed her. “I had taken a stand for my people,” Colvin says in the book. “I had stood up for our rights. I hadn't expected to become a hero, but I sure didn't expect this. I cried a lot, and people saw me cry. They kept saying I was 'emotional.' Well, who wouldn't be emotional after something like that? Tell me, who wouldn’t cry.”

Eventually, the courts ruled Montgomery's bus policy unconstitutional. The battle for civil rights dragged on, but without Colvin. She became a historical footnote, a trivia question, a paragraph in a book. “I didn't like the way she was portrayed,” Hoose says. “It was an affront to all teenagers who stuck their necks out.”

Colvin's resistance underscores the courage of many African-American women who struggled during the civil rights era. Most worked behind the scenes demanding a social revolution. Yet, they too felt the pain of Bull Connor's dogs, and the agony of the fire hose. Not only did these women feel the smack down of racism, but the sting of sexism from male civil rights leaders.

“They weren't just living in a racist society, but a patriarchal society,” says Williams. “The great American hero is the great American male hero. Many of the narratives put men in the forefront. Claudette Colvin was a young woman – technically, not a woman yet – but galvanized by the spirit of her teachers who were also women.

“Hers was the first documented, very public case in Montgomery that began to galvanize people,” Williams says. “Also remember, a lot of domestics, who were women, and who rode the buses, were suffering indignities daily. What happened to Claudette Colvin and later Rosa Parks was not only familiar, it resonated.”

Now 70, Colvin is a retired nursing home worker living in New York City. Her phone number is unlisted and she doesn't have a computer. She rarely ventures outside her neighborhood. Hoose now counts the one-time feisty teen, as a friend, something that would have been impossible when the two were younger.

“We would not have had an opportunity to know each other all those years ago,” Hoose, 63, says. “That is one of the things that gets lost…two groups of people didn't get a chance to know each other just as friends. They didn't know what they were missing. I'm so glad I got to know her.”