There were many triggers for the Civil War: Slavery, sectional rivalries, and the assault on Fort Sumter. However, one that is not as well known is the explosive case of Sara Lucy Bagby – the last African-American prosecuted under the Fugitive Slave Act.

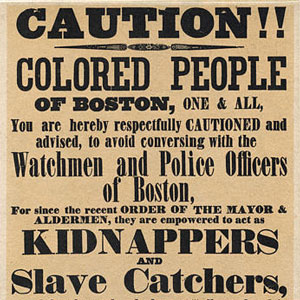

The Fugitive Slave Act was a lightning rod for controversy in the on-going slavery debate ever since its passage in 1850 as part of the Compromise of 1850. The Compromise of 1850 was a series of five bills designed to quell the growing strife between the North and South. Routinely ignored by Northerners, the Fugitive Slave Act was intended to strengthen the previous Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. The new law compelled federal judicial officials in all states and territories, even those that prohibited slavery, to assist in the capture and return of a suspected fugitive slave or pay a fine of $1,000 (big money in those days). It also compelled ordinary citizens to serve in a posse for the capture of the slave, and assist in the return of said slave.

Even Northerners lukewarm on the issue realized they could be forced, at any time, to support slavery and forced to choose sides by helping slavery or hindering it.

Into this hornet’s nest stepped Bagby.

Bagby, pregnant and in her early 20s, fled from her master in Wheeling, Virginia in October 1860. She made it to Cleveland, Ohio, a region and state that was a hotbed of anti-slavery activity. (It was no accident that Harriet Beecher Stowe selected Ohio as a destination of freedom in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.) There Bagby found work as a domestic servant in the home of an anti-slavery jeweler named L.A. Benton.

On the morning of January 19, 1861, two U.S. Marshals and Bagby’s former owner, the Reverend William S. Goshorn, pounded on Benton’s front door. Frantically, Bagby tried to hide in an upstairs bedroom, but the men found her and dragged the terrified woman to jail.

On the morning of January 19, 1861, two U.S. Marshals and Bagby’s former owner, the Reverend William S. Goshorn, pounded on Benton’s front door. Frantically, Bagby tried to hide in an upstairs bedroom, but the men found her and dragged the terrified woman to jail.

The news of Bagby’s arrest raced across the country. It was as if the South had stabbed the North in the heart; Bagby was snatched from a bastion of freedom by the evil slave oligarchy. Northerners now knew that slave-owners would indeed reach into any town in any state and grab any African-American they chose. No one was safe from slavery’s odious grasp.

In the days before Bagby’s trial, the street outside her jail nearly erupted into violence several times as free blacks gathered. Others pleaded for calm. The United States in early 1861 was in a tenuous position, with some states having seceded and others mulling the possibility. Many hoped that there was still a way to reunite the country. But a violent rescue of Bagby would further inflame the South and make disunion inevitable.

“No, colored citizens, do not undertake such a rash act [rescue],” counseled a newspaper. “…show to the world that you are possessed of noble qualities…” Clevelanders showed Goshorn and his father every kindness. No one wanted to tip the balance between union and disunion.

Bagby’s trial was brief. The outcome a foregone conclusion, especially when Goshorn produced documentation that he paid $800 for her and Bagby admitted that she had belonged to him. Her lawyer wondered that as Cleveland allowed her to be returned into bondage, would not “…the frantic South stay its parricidal arm? Will not our compromising legislators cry, ‘Hold, enough!”

The Goshorn's denied a last ditch attempt by Clevelanders to buy Bagby’s freedom (even the arresting marshal pledged $100) because of their determination to make their point that the law could and should be enforced.

Sullen blacks watched Bagby taken to the train station; they would not interfere. Armed deputies stood alert for trouble; a crowd of liberators gathered at Lima, but the episode came to naught. Bagby continued her sad journey back into captivity. The North was left stunned, to contemplate how it had let a black woman quietly minding her own business in a free society be dragged back into slavery.

Sullen blacks watched Bagby taken to the train station; they would not interfere. Armed deputies stood alert for trouble; a crowd of liberators gathered at Lima, but the episode came to naught. Bagby continued her sad journey back into captivity. The North was left stunned, to contemplate how it had let a black woman quietly minding her own business in a free society be dragged back into slavery.

A little over one year later, Union troops entered Wheeling, and Bagby was free once more. She returned to Cleveland in 1863, where African-Americans organized a celebration for her. She married F. George Johnson, a former Union soldier, and lived in Pittsburg until returning to Cleveland later in life. Bagby died on July 14, 1906, she was buried in Cleveland’s Woodland Cemetery, where her headstone reads “Unfettered and Free.”

The Bagby case received international publicity as America teetered on the brink of Civil War. Many say that her high-profile prosecution proved to the North that they had to make a stand - that repeated compromises would never satisfy the South. If so, then Bagby is a significant (yet sadly ignored) African-American hero, for she helped put them on the road to freedom.

Sources

1. “1861 – The Civil War Awakening” by Adam Goodheart

2. http://ech.case.edu/ech-cgi/article.pl?id=BFSC

3. http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/trailblazers/2010/honoree.asp?bio=3

4. http://blog.cleveland.com/metro/2011/11/a_headstone_for_the_unmarked_g.html

5. http://wheeling.weirton.lib.wv.us/history/people/others/lbagby.htm