Skull and crossbones accessories, black lace gloves, ghostly pale makeup and a black diamond-encrusted bra: Not the traditional kind of costume most of us expect a belly dancer to wear, unless of course, you’re watching Aepril Schaile perform Gothic belly dance.

Schaile is part of a new phenomenon that mixes traditional Middle Eastern belly dancing with elements of so-called Goth culture. Yet, this fused dance form has outraged some purist dancers who say the new fad exploits traditional Middle Eastern culture.

“Gothic may be good for a horror movie, but it is not belly dancing. It consists of strange posing, non-Arabic music, black lipstick and basically has no real resemblance to Middle Eastern dance at all. It’s sort of posing,” says Soraya el-Khouby, a Middle Eastern dancer of Syrian descent. She prides herself on practicing what she says is “authentic” belly dance and is worried that the new style may create an MTV-ized version of a dance that’s highly prized in her heritage.

“Gothic may be good for a horror movie, but it is not belly dancing. It consists of strange posing, non-Arabic music, black lipstick and basically has no real resemblance to Middle Eastern dance at all. It’s sort of posing,” says Soraya el-Khouby, a Middle Eastern dancer of Syrian descent. She prides herself on practicing what she says is “authentic” belly dance and is worried that the new style may create an MTV-ized version of a dance that’s highly prized in her heritage.

Schaile, whose heritage is Irish and German, admits that a lot of the people interested in the new style are middle class, educated white women, but believes that with a correct history lesson, she can help expose people to an ancient art form.

“People that want to stay traditional say that this is bastardization. It’s a moot point,” she says. “It’s always going to be valid. Gothic belly dance is about exploration of the traditional.”

The debate over whether Gothic belly dance is being exploited by “cultural tourists” who may be co-opting Middle Eastern culture is only one example of “cultural hijacking” that has become commonplace in a changing America.

Globalization, a rapidly growing immigrant population, as well as the Internet, have dramatically increased American’s exposure to and interest in traditional cultures other than their own. Cultures increasingly clash and co-mingle without most of us realizing it. Think of that falafel sandwich you had for lunch, the anime cartoon your kids watched on TV, or the jazz on your radio — each an expression of a unique ethnic or national culture, yet entirely common in contemporary American life.

Globalization, a rapidly growing immigrant population, as well as the Internet, have dramatically increased American’s exposure to and interest in traditional cultures other than their own. Cultures increasingly clash and co-mingle without most of us realizing it. Think of that falafel sandwich you had for lunch, the anime cartoon your kids watched on TV, or the jazz on your radio — each an expression of a unique ethnic or national culture, yet entirely common in contemporary American life.

While many argue that these cultural influences are essential to the creation and evolution of a multicultural society, there are still sensitivities about how much one can “dip” into a culture without exploiting it. A recent upswing in trends, like black kids getting Asian-inspired tattoos, white kids dreadlocking their hair, and Korean kids wearing Afro hairstyles have sparked heated debates about cultural tourism.

“Cultural tourism” is when people “visit” or “explore” traditions and customs other than their own.

Since no one culture can technically “own” particular aspects of an identity, the issue is a thorny one, particularly in America, where cultures have mixed since the Mayflower landed at Plymouth Rock.

American culture is, at its core, an amalgam of traditions that have been “hijacked” from other cultures and assimilated — i.e. hot dogs (from German sausages), jazz (from West Africa), and graffiti (from ancient Rome), which all have foreign roots.

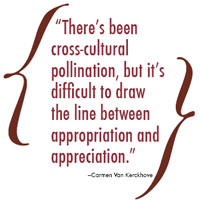

“There’s been cross-cultural pollination, but it’s difficult to draw the line between appropriation and appreciation. People don’t mind appreciation, but it’s difficult to tell when it crosses. White kids with Chinese tattoos can seem offensive, because it doesn’t seem like there is much appreciation,” says Carmen Van Kerckhove, the founder and president of New Demographic, a diversity consulting firm.

For example, there are almost 30,000 Chinese restaurants in the United States, making Chinese food among the most popular in the United States. But if you ask the average American who Hu Jintao is, they may balk.

For example, there are almost 30,000 Chinese restaurants in the United States, making Chinese food among the most popular in the United States. But if you ask the average American who Hu Jintao is, they may balk.

Philip Yu, a Korean-American youth, started the website angryasianman.com, to help people appreciate Asian culture beyond cuisine and tattoos.

“In popular culture, people tend to pick and choose what’s ‘cool’ about Asian culture, without really understanding the history and significance behind it. I can’t fault a non-Asian guy for really being into Hong Kong martial arts movies, because I love them and I’m certainly not Chinese. But there are also those who pick and choose aspects of Asian culture because it’s a fad or it’s trendy. And at the end of the day, they have no idea what it’s like to be Asian.”

Like Yu, some academics are worried that the popularity of more superficial aspects of different cultures distracts from the historical and political significance of those cultures.

“Just because white people were putting on black face 100 years ago didn’t mean that we didn’t have slavery or segregation. White kids wearing dreads and liking hip-hop doesn’t mean that racism doesn’t exist, but people use it to make that claim,” says Professor Woody Doane, a sociology professor at the University of Hartford and editor of the book White Out: The Continuing Significance of Racism.

Doane says just because globalization, television and the Internet have made other cultures more accessible, it doesn’t mean it’s leading to a total integration of cultures.

A 2005 study by the Boys and Girls Club of America and the Allstate Foundation found that while 84 percent of youth said they had friends of different ethnicities, only 55 percent of girls and 44 percent of boys said they were actually comfortable with other races.

“Take the kid that’s listening to hip-hop and wearing dreadlocks; is that going to change where he buys his first house? Or is he going out to suburbia? I don’t want to sound like a cynical old man, but I think he goes out to suburbia,” says Doane.

“Take the kid that’s listening to hip-hop and wearing dreadlocks; is that going to change where he buys his first house? Or is he going out to suburbia? I don’t want to sound like a cynical old man, but I think he goes out to suburbia,” says Doane.

Van Kerckhove says cultural tourism can distort one’s perception of racial tolerance. “This generation assumes they’re less racist. They think they’re beyond race because they have black artists in their iPod.”

The reasons why people decide to adopt customs from other cultures are as diverse as the cultures themselves. Some critics say it’s because people are unsatisfied with their own culture. But Schaile says that experimenting with belly dance allowed her to fuse her love of dance with Gothic culture.

Then there are others who say cultural tourism just isn’t that deep or profound.

Jenna B. is a hair stylist in the Philadelphia area who specializes in dreadlocks and hair extensions. She says many white people, like herself, who get dreadlocks, a style that is often associated with African and Afro-Caribbean cultures (but actually has roots in Greece and India) do so not to make a political statement, or to exploit a culture, but simply for convenience. “Some people do it more for fashion, some do it because they’re just, like a plain-Jane and it gives them style. Some just don’t want to deal with their hair.”

David Hollinger, a professor of American History at the University of California-Berkley and author of Postethnic America: Beyond Multiculturalism, says that the importance of cultural tourism is often over-exaggerated. “Cultural tourism, unless carried out with gross insensitivity, such as the old blackface routines of white comedians a century ago, is a sign that the person doing the ‘touring’ is less hostile toward the group in whose company the ‘tour’ is being made. When someone from group X appropriates a symbolic representation of group Y, it is a compliment of sorts, but not one that carries heavy obligations. It is a light, congenial way to express an element of solidarity with people whose background is different from one’s own.”

David Hollinger, a professor of American History at the University of California-Berkley and author of Postethnic America: Beyond Multiculturalism, says that the importance of cultural tourism is often over-exaggerated. “Cultural tourism, unless carried out with gross insensitivity, such as the old blackface routines of white comedians a century ago, is a sign that the person doing the ‘touring’ is less hostile toward the group in whose company the ‘tour’ is being made. When someone from group X appropriates a symbolic representation of group Y, it is a compliment of sorts, but not one that carries heavy obligations. It is a light, congenial way to express an element of solidarity with people whose background is different from one’s own.”

As an African-American woman who has dealt with hair issues, Regina Walton says imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. She was working overseas when she first saw Korean youth wearing chemically created Afros and dreadlock styles.

“Something in black culture has probably touched them and they want to express their love for it through how they look. Their reasons for wearing dreads or Afro perms are probably very different from why I wear my hair natural. To me, I think nothing much of it. It’s how they’ve chosen to wear their hair.”

However, Doane cautions people to ask themselves why they’ve taken an interest in these other cultures. “If you think about it, why would one of us want to put on a Chinese tattoo? Because it sort of gives us the appearance of being worldly, sophisticated, even when we’re maybe not. It’s a quick way. Instead of really understanding Chinese culture, we just get a tattoo.”

Doane says that when cultural tourism turns into appropriation or hijacking, the results can wreak havoc on the originating culture. “The danger is that so much of what we do becomes commercialized and commodified.”

For years, cultural appropriation has been highly profitable in American society. Think of the millions Elvis Presley made from imitating the black singing and performing style in his first hit song, “Hound Dog,” while Big Mama Thorton, the original singer of the song only received $500 for her version.

For years, cultural appropriation has been highly profitable in American society. Think of the millions Elvis Presley made from imitating the black singing and performing style in his first hit song, “Hound Dog,” while Big Mama Thorton, the original singer of the song only received $500 for her version.

“We all hijack all the time — cultural diffusion. What changes is when you bring power into the equation. Whites kind of hijacked the blues, and were able to profit. It turns into cultural imperialism when BB King and Muddy Waters were introduced to America by the Beatles,” says Doane.

Yu says Asian culture is often used for commercial purposes in the United States. He is still is angry over an ad a Rhode Island restaurant used to promote their new fusion hotspot. The ad used a picture of a naked woman with an Asian tattoo, along with the words, “See what you’re missing.” He says the ad played right into the whole Asian exotic stereotype. What’s worse, he notes, is that an actual Chinese-owned laundry shop used to sit on that property.

“The whole thing is just exploitive appropriation to me. It plays on the sexualized stereotype of the submissive Asian woman. It’s also selectively taking aspects of Asian culture, including the female Asian body itself, and creates a product and atmosphere around it. What this naked female body with an Asian tattoo has to do with food, I have no idea.”

El-Khouby, however, says she’s not worried about groups profiting from cultural tourism. She’s more concerned about the distortion of her heritage. She says Gothic belly dance takes the traditionally positive nature of a dance form and turns it on its head. “Gothic belly dancers don’t really want to learn the tradition. It’s very specific and it takes a lot of understanding. You have to understand the language and the music. You have to understand the ideology of the culture and learn how to connect with it.”

Schaile says it’s mandatory that all of her students participating in gothic belly dance learn the Middle Eastern roots that belly dancing is based on. “I’m glad for people that want to fuse tradition, but also for those that want to keep tradition, so you have standards and guardians of that; it all keeps the whole thing beautiful.”

Hollinger does not think that the cultural exploration trend will lead to the eradication of ethnicities in favor of one superculture any time soon. “It does not mean that lines between ethno-racial groups are disappearing, but it does mean that there is more blurring.”

Instead of focusing on the negative aspects of cultural-hijacking and appropriation, Doane says it’s imperative to capitalize on the benefits of globalization. “I think we have an opportunity to become citizens of the world, because the world has become smaller, but it’s how we use that opportunity. If we consume stereotypes in an atmosphere of ignorance, it can become more harmful. If we learn about other people and other cultures and their social context, then cultural tourism can become a vehicle for real understanding.”