Voting is being emphasized in Ferguson, Missouri after the shooting death of Michael Brown by a member of a nearly all-white police department. Ferguson is nearly 70% black. Increased voting will be one of the ways to increase black representation in city government as well as law enforcement.

Political participation is increasing on the national level for blacks and Hispanics. On the local level, voting continues to be a struggle, as it is in this St. Louis suburb.

In the most recent city election in April, only 1,484 of Ferguson's 12,096 registered voters cast ballots, easily re-electing the mayor. Next year voters can weigh in again on their municipal government through city council elections.

Nationally, only 1 in 4 four voters turns out for mayoral elections in the largest cities, according to a 2013 study of 340 mayoral elections in 144 cities from 1996 to 2012 by Thomas M. Holbrook and Aaron C. Weinschenk of the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee and the University of Wisconsin Green Bay.

Missouri does not ask about race or ethnicity on its voter registration forms. But roughly two-thirds of Ferguson's residents are black. The police force is predominantly white. Five of Ferguson's six city council members are white, as is the mayor. The grand jury investigating the Brown case has six white men, three white women, two black women and one black man.

Lifelong Ferguson resident Andre Adams, 29, a barber at Infiniti Styles Barbering Salon, said he votes whenever he can. Young people in Ferguson must be convinced that they should do the same, Adams said, or "we're just going to fall victim to what's going on now."

"We need more of our young people, as well as our old people to come out here and vote, to get what's going on, to listen in to the town hall meetings and all," Adams said. "If we could get them, something could actually change."

There are signs that residents are ready to reverse years of civic apathy. At the city council's Sept. 9 meeting, the first since Brown was killed, resident after resident pledged to vote Mayor James Knowles and council members out of office, sharply rejecting earlier assertions by Knowles that there was no "racial divide" in Ferguson.

Attention to minority participation in civic life has increased since Aug. 9, when Brown was shot multiple times by Officer Darren Wilson, and died in the street. Protests followed, sometimes marred by rioting and looting that was met with tear gas and rubber-coated bullets from police.

The city largely has been calm since Brown's Aug. 25 funeral, except for demonstration Wednesday when protesters were arrested while trying to shut down traffic on Interstate 70. Brown's family has appealed for people to get involved. "Show up at the voting booths. Let your voices be heard, and let everyone know that we have had enough of all of this," said Eric Davis, one of Brown's cousins, at the funeral.

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, a civil rights leader whose voter registration efforts helped bring about the election of the first black mayor of Chicago in 1983, spent time in Ferguson trying to register people to vote following Brown's death. Jackson, who ran for the White House in 1984 and 1988 and says his campaigns were responsible for registering 3 million new voters, said minority voters had to be educated on how the nominating process works so they could become part of it.

Jackson said he tried to explain to Ferguson residents why it matters to participate in elections at all levels. "People didn't realize that they couldn't be on a grand jury if they didn't vote," Jackson said. "They didn't realize that by voting for mayor, they could have a say on who the police chief was, who makes up the police force. People didn't know they could vote in and out of office the judges that hear these kind of cases."

Rita Heard Days, director of elections in St. Louis County, said her office has seen a noticeable increase in voter registration cards from Ferguson and surrounding areas since Brown's death. "We've got a lot of people who have contacted us from that area wanting to have voter registration drives," she said.

Increased local participation would match growing minority participation in national and state level politics. In presidential election years, the percentage of black voters eclipsed the percentage of whites for the first time in 2012, when 66.2 percent of blacks voted, compared with 64.1 percent of non-Hispanic whites and about 48 percent of Hispanics and Asians.

Blacks and non-white Hispanics are the only groups to have increased their participation in midterm elections, voting at 38.6 percent and 19.3 percent, respectively, in the 2006 congressional and statewide elections, and at 40.7 percent and 20.5 percent, respectively, in 2010.

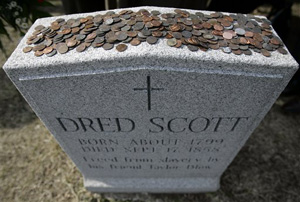

A few miles from the street where Michael Brown died is the grave of Dred Scott, a slave who went to the Supreme Court and tried, unsuccessfully, to be recognized as a free American citizen.

One hundred and fifty-seven years later, a white police officer's fatal shooting of Brown - unarmed, black and 18 years old - raises fresh questions about the extent to which blacks in suburban towns are regarded as full partners by the officials and law enforcers elected largely by and responsive to small segments of the population.

Follow Jesse J. Holland on Twitter.

Copyright 2014 The Associated Press