Of all the components that make up American cities, none has more impact on a city’s sense of community, prosperity, and public life than its streets.

As transportation arteries, streets have the capacity to unify disparate groups, allow people to move with relative freedom from one part of town to another, yet, these same streets may also serve to divide and isolate. In the days of legal segregation – and not just in the Jim Crow South – streets in many cities across the country separated citizens by race, class, and ethnicity. Although a strip of asphalt is hardly an impenetrable barrier, a street can still divide neighborhoods as effectively as a concrete wall once separated East and West Berlin.

“In some ways, streets are like our social mirrors,” says Derek Alderman, a cultural geographer at East Carolina University in Greenville, South – North Carolina. “They point where we come from and they also point where we are going. Not just literally, in terms of direction, but in terms of where we are socially.”

Historically, nearly all cities with diverse populations had streets that served as racial, ethnic or class dividing lines. In some cities, various forces caused the lines to shift, so over time different streets formed the boundary. In other cases, particularly in fast growing cities with strong economies, these streets-cum-barriers were obliterated by sheer economic development pressure and gentrification. In still other cities, the borders separating one group from anther are composed of several streets, so there is no stigmatization of single streets as dividing lines.

However, in several American cities today, a variety of social, governmental, geographic, and economic forces have converged to turn a single, major street into a racial boundary line. In at least three instances, these streets as boundaries have become so deeply etched into the psyche of their respective cities that their divisive characters – both real and symbolic – remain firmly entrenched more than a half-century after legal segregation ended in the United States.

Main Street – Buffalo, New York

Main Street in Buffalo is (as the name implies) the primary commercial thoroughfare that runs through downtown Buffalo and extends to the south. Historically, Main Street has served to divide the city of Buffalo, not just east from west, but Catholic from Protestant, immigrant from native-born, affluent from working class, and poor. In recent decades, it also divided black from white. The fact that it is by far the widest street in town – just less than 100 feet at its widest point, even makes it look like a barrier.

“Main Street is as old as Buffalo,” businessperson and historian Mark Goldman wrote in his 1990 book City on the Lake. “It was this street, which many now consider ugly and depressing, that for so many years, like a racial Maginot Line, has served to divide the East Side from the West Side.”

Main Street’s roots as a dividing line reach back to the city’s 19th century beginnings. The west side of Main evolved primarily as a residential community where the upper and middle classes lived, along with the higher paid workers. The 1933 Real Property Inventory of the City shows that monthly rentals on the west side of Main were the highest in Buffalo.

From the beginning, the area east of Main developed much more slowly. Industrial centers took hold on Buffalo’s east side by the late 1800s, along with inexpensive housing for the area’s principle residents – recent European immigrants and the city’s small community of African-Americans. The post-World War II era saw the rapid growth of the suburbs as well as that of the black community, which gradually supplanted the white ethnic enclaves east of Main.

Although Goldman compared Main Street to the French Maginot Line in 1990, he does not believe the comparison is accurate today.

“The African American population has spread everywhere,” Goldman said in a recent interview. “The majority of blacks in the city of Buffalo certainly live east of Main Street, but all the schools in the city have predominantly black student populations. I don’t think Main Street is a boundary in anybody’s mind any longer.”

Not everyone agrees. Donn Esmonde, Buffalo News columnist, says Main Street continues to be the dividing line between black and white Buffalo.

“When people talk about the East Side – which, geographically, refers to the east side of Main Street – it is essentially a synonym for African-American Buffalo,” he says. “There are parts of Main Street where the divide is essentially a line of demarcation, where the divide is very dramatic. Where the houses on the west side are valued at $350,000, which is a lot for Buffalo, and two blocks over on the east side, the housing stock is next to worthless.”

Henry Taylor, director of the Center for Urban Studies at Buffalo State University of New York, agrees that Main Street is still, at least symbolically, a dividing line, although to a lesser degree than in the past. He argues that even though African-Americans have migrated to the west side of Main Street, the migration of whites to the east side has been minimal. Likewise, he says, it’s a well known fact that the overwhelming majority of whites who choose to remain in the city live on the west side of town, where the quality of housing is higher, where housing appreciates faster and where the built environment – parks, boulevards, historic houses – speak of vastly higher living standards.

“When you say you live on the east side, people automatically see the negative,” Taylor says. “If you say you live on the west side, people just assume you’re living better than if you said you live on the east side. Main Street remains that dividing line, that space that separates two worlds, not just between black and white, but between a better life and a worse life.”

Taylor also notes that streets that divide by race are first dividing by class. “Money dictates where you live,” he says. “Race is an overlay of class, because where you live in the city is first and foremost dictated by the cost of housing. It’s only secondarily influenced by the issue of your color.”

Taylor believes Main Street’s psychological power is diminishing, but not necessarily for positive reasons. “The city of Buffalo, as a whole, is under such siege and its problems are so great, in a lot of ways the tremendous symbolism that used to be characteristic of Main Street has now been replaced by the suburbs,” he says. “It’s ironic. Now people on both sides of Main have become partners in a quest to save the city from its real enemy, which is economic decline and the failure of metropolitan leaders – both city and suburban – to formulate the creative policies necessary to halt the slide.”

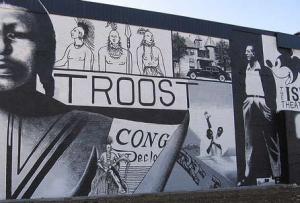

Troost Avenue – Kansas City, Missouri

If the Maginot Line is a frequently invoked topic of discussion regarding Buffalo’s Main Street, the Berlin Wall is a metaphor often employed when discussing Troost Avenue and the way it has divided black and white Kansas City, Mo., for decades.

If the Maginot Line is a frequently invoked topic of discussion regarding Buffalo’s Main Street, the Berlin Wall is a metaphor often employed when discussing Troost Avenue and the way it has divided black and white Kansas City, Mo., for decades.

The street, named for Benoist Troost, a 19th-century physician, entrepreneur and city father. Troost was a prosperous commercial thoroughfare and highly desirable residential area in the early 1900s. In the years following World War II – a period that was hard on most urban centers in the United States – a number of forces converged to cause the fortunes of Troost Avenue and the neighborhoods to its east to plummet in a relatively short period.

By the 1960s, the ten-mile avenue, which cuts through the east side of Kansas City, running north and south from downtown to the city’s southern reaches, was ravaged by crime, poverty, racial discrimination, abandoned buildings and other problems. Worse, the avenue became a racial and economic dividing line – both real and symbolic – in a city slow to shake off its segregated past, with poor blacks living east of Troost and middle-to-upper-class whites living west. In time, “East of Troost” became a loaded phrase as the street’s very name came to epitomize everything wrong with race relations in Kansas City.

Kevin Fox Gotham, professor of sociology at Tulane University is the author of Race, Real Estate, and Uneven Development: The Kansas City Experience, 1900-2000 (State University of New York Press). Gotham became interested in Troost Avenue because as recently as the late 1990s there were discussions about it being an important dividing line.

“In people’s minds and in the urban culture as a whole, Troost was still very much seen as a dividing line,” he says.

Gotham cites three factors that came into play in Kansas City that caused Troost Avenue to evolve into a racial dividing line. The first was large-scale slum clearance and highway relocation programs between the 1950s and early 1970s. Led by various government agencies, these programs resulted in huge numbers of east side residents being funneled into the local housing market – with blacks generally crowding into already substandard neighborhoods in the eastern part of town and whites moving into new housing in the burgeoning suburbs.

The second factor, according to Gotham, was a stratagem devised by the Kansas City, Mo. School District, to preserve segregated schools in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, outlawing school segregation. With the African-American population of Kansas City largely settled east of Troost Avenue, the school district was able to maintain segregated schools by making Troost the attendance boundary, with white schools on the west and black schools on the east. The plan succeeded; no racially mixed schools opened in Kansas City from 1955 until the 1970s, except for some transitional schools in the process of become becoming either all black or all white. In the process, Troost, established as a racial dividing line, a predicament that remained and became more deeply entrenched as time passed.

The displacement of east side residents by urban renewal and the school district’s use of Troost Avenue as an attendance boundary set in motion a vicious wave of real estate blockbusting says Gotham.

“Real estate blockbusting depended upon the school district using Troost Avenue as a racial attendance boundary and essentially abandoning its schools to the east to the expanding black community,” says Gotham. “It also depended on the opening up of the suburban housing market, which was pretty much run by white real estate agents and firms, who indirectly benefited from blockbusting.”

Although blockbusting, redlining and similar practices are now illegal, the east side’s downward economic spiral – lower incomes, higher unemployment, and lower property values – is extremely difficult to reverse. As property values drop, so does residents’ access to capital, severely limiting reinvestment in the community through home improvement loans and the like.

“That’s a double-whammy for African-Americans, since they tend to be more concentrated in areas where there are lower incomes and lower property values,” says Kansas City historian William Worley. “Sadly, discrimination on the basis of income and property values is not illegal. In fact, it’s encouraged.”

Though the economic realities of the Troost corridor pose an enormous obstacle, there are indications that things are changing for the better along the ten-mile stretch. Efforts by neighborhood associations, small businesses, large institutions, and individual residents aiming to bring new life to the area are in evidence. While Troost clearly has a long way to go in reversing a half-century of segregation, discrimination, and decline, there are reasons to be hopeful for Troost Avenue and the surrounding neighborhoods.

8 Mile Road – Detroit, Michigan

No street name in the United States is more synonymous with racial and class division or saddled with more negative baggage than 8 Mile Road, which forms the northern boundary of Detroit and the southern boundary of suburban Macomb and Oakland counties. In 2002, rapper Eminem made the name 8 Mile familiar to many in his semi-autobiographical movie of the same name. However, the eight-lane road has long had a reputation as a physical and psychological dividing line, separating black from white, rich from poor, symbolizing the death of American cities and white flight to the suburbs. As British journalist, Paul Harris observed a few years ago, “It is both a physical barrier and a psychological one. Crossing 8 Mile Road is not as easy as dodging traffic.”

As a county line, 8 Mile has always been a civic dividing line. It was not until after World War II that it became a racial dividing line as well, when white residents of Detroit began a steady exodus from the city to the surrounding suburbs. That exit became a stampede after the riots of 1967.

The late 1960s saw devastating riots in many large cities, but in Detroit, the riots created the most psychological damage in the country. Some say the wounds are still present. The 1967 riots created a racial atmosphere in Detroit that became deeply polarized and 8 Mile Road took on even greater significance.

“There’s no question that 8 Mile Road is a phrase laden with meaning in metropolitan Detroit,” says Gregory Sumner, professor of American history at University of Detroit Mercy. “I think in the 1970s it was a radioactive phrase. It has this kind of mythic power as a dividing line, which is a major part of metropolitan Detroit’s identity.”

In the decades since the riots, the steady decline of the automobile industry, along with crime, poor schools, lack of city services, and other big-city ills have taken a toll on Detroit. The city has lost more than half its population since the 1950s (from two million to less than 900,000). South of 8 Mile – an eight-lane road lined with pawnbrokers, sex shops, topless bars, fast food joints, and motels with both hourly and weekly rates – the city is overwhelmingly poor and black. Unemployment is among the highest in the nation and roughly one in three Detroiters live below the poverty line. North of 8 Mile, the demographic is nearly the exact opposite – overwhelmingly white and middle-class, with low unemployment and household incomes double of those to the south.

Today, some communities north of 8 Mile have substantial minority populations. (Southfield, for instance, is 54 percent African-American. Dearborn is 30 percent Arab.) If 8 Mile is not the dividing line it was in the past, it remains very much a psychological divide.

“It’s a symbolic dividing line for people in the suburbs as well,” says Charles Hyde, professor of history at Wayne State University in Detroit. “There are former residents of Detroit who moved out in the 1950s and ‘60s that will proudly say they have not been south of 8 Mile in 30 years.”

Neighborhood coalitions and community groups, like the 8 Mile Boulevard Association, an organization of public and private sector members from some 16 cities bordering 8 Mile, are trying to reverse this. Sumner sees hopeful signs of change and improvement, like a modest revival underway in Detroit, with loft conversions, an active art community, an entertainment district, and young people who do not have the same baggage about the city as their elders, moving downtown.

“There’s a dynamism going on,” he says. “There are a lot of good things going on that are not visible to the casual, outside observer. People, and particularly young people, are hungry for that new urbanism. It’s blossoming.”